The Elizabeth Street Veterinary Clinic (ESVC) dates back to 1813 when Joseph Sewell MRCVS, an equine vet and his son Frederick moved their business to Elizabeth Street and called it ‘The Infirmary for Horses and Dogs’.

Two more generations of Sewells followed, Alfred Sewell MRCVS, a recognised authority on how to control rabies in dogs and his son Louis Sewell MRCVS an expert on distemper. In 1901, the first non-Sewell, Frederick Cousens MRCVS, founder of the ‘French Bulldog Club of England’, joined the business and shortly after, the Veterinary Infirmary became one of the first in the world to have its own x-ray facilities. ESVC provided pro bono veterinary care to both ‘Battersea Dogs Home’ and ‘Our Dumb Friends League’, now the ‘Blue Cross’.

In the 1930s Denys Danby MRCVS joined the practice. He developed an anaesthetic mask for dogs, used by vets for the next 30 years. Judith Iffey MRCVS purchased the business in 1960. In 1980 Keith Butt, Andrew Carmichael, Bruce Fogle and Michael Gordon acquired the surgery and Elizabeth Street became the first clinic in Europe to offer 24 hour staffed emergency care for animals.

The Sewell family start the ‘Veterinary Infirmary‘

The Elizabeth Street Veterinary Clinic (ESVC) has a long, distinguished history and may be the oldest, continuously operating veterinary facility, in the United Kingdom.

The history of the Clinic begins in 1813 when Joseph Sewell graduated from the Royal Veterinary College. He first practiced from ‘The Veterinary Stables’ at 10 Water Street, Strand.

Frederick Sewell, his son, graduated in 1839 and joined his father at the ‘Infirmary for Horses and Dogs‘, now at 32 North Row, Park Street, Hyde Park. Soon after, Frederick moved the horse and dog infirmary to 21 Elizabeth Street. We have served the local community in Belgravia from Elizabeth Street for over 180 years.

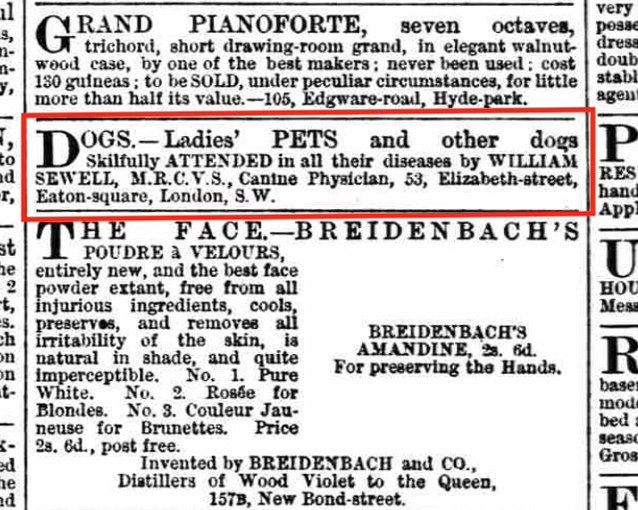

William Sewell, Frederick’s older son graduated in 1870 and joined his father who was now at 53 Elizabeth Street. William placed adverts in The Times and The Morning Post for ‘Ladies’ PETS and other dogs. Skilfully ATTENDED in all their diseases by WILLIAM SEWELL, MRCVS, Canine Physician…’

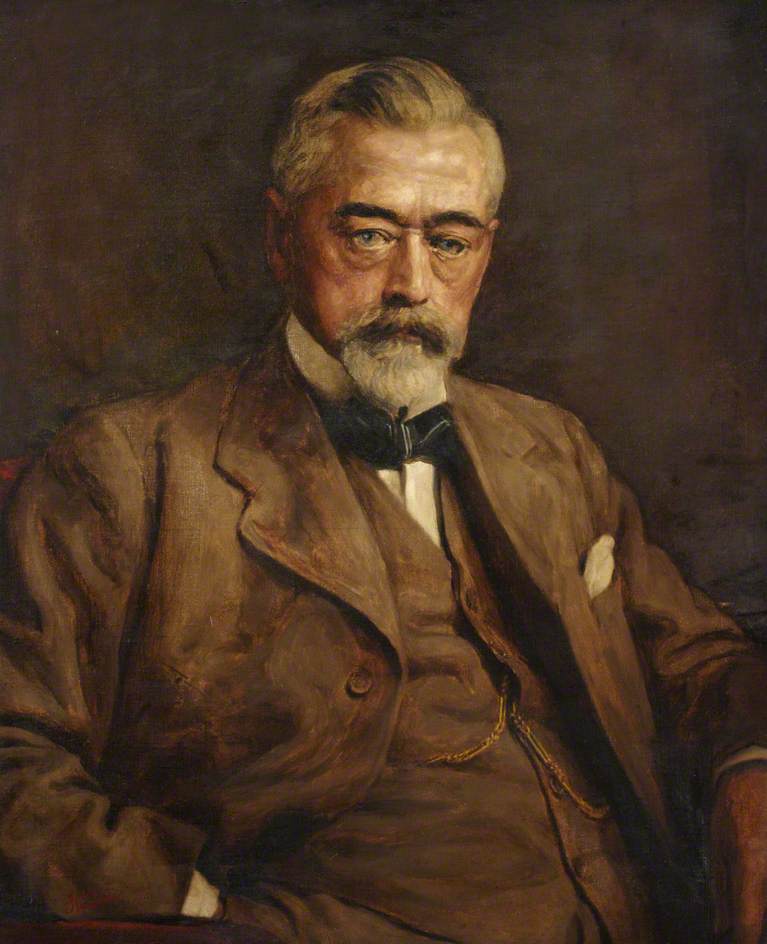

Alfred Sewell, William’s younger brother, graduated in 1877 and became the most illustrious member of the Sewell family of veterinary surgeons. The father and sons practiced jointly at ‘The Veterinary Infirmary‘ at 51A, 53 and 55 Elizabeth Street.

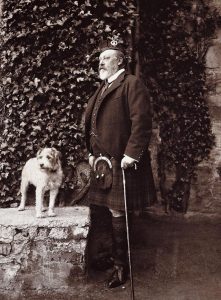

Alfred Sewell was the first veterinary surgeon at ‘Battersea Dogs Home’, ‘The Kennel Club’, and ‘The Dumb Friends’ League, now the ‘Blue Cross’. He became by Royal Warrant, Veterinary Surgeon to the Prince and Princess of Wales.

Elizabeth Street Vets and Animal Welfare

In the 1870s, the Elizabeth Street vet, Alfred Sewell, provided veterinary services free of charge to ‘Battersea Dogs Home’. In 1905 when ‘Our Dumb Friends League’ (which later became the ‘Blue Cross’) was founded, both Alfred Sewell and his partner, Frederick Cousens extended their pro bono services to the charity.

Alfred Sewell’s involvement in what came to be called ‘The Brown Dog Affair’, reveals his keen interest in animal welfare.

The Brown Dog Affair

At the turn of the 20th century, vivisection, or operating on live animals for scientific reasons, was considered ‘normal’. The Brown Dog Affair revolved around experiments in 1903 on a six kilo terrier at University College London. Two Swedish students had enrolled specifically to bring these experiments to the attention of the public and the surgeon in charge, Dr William Bayliss, was publicly accused of vivisection. Bayliss brought a case of libel against his accuser, Stephen Coleridge.

Bayliss retained as his expert witness, the Principal of the Royal Veterinary College, Frederick Hobday, argued that he acted humanely. Stephen Coleridge’s expert witness, Alfred Sewell the Elizabeth Street veterinary surgeon, claimed that the dog was not properly anaesthetized.

Dr. Bayliss, the surgeon, said he had given the dog chloroform and ether delivered by pump into a tube connected to the dog’s trachea and had killed the dog with chloroform. However, the Swedish medical students said that they couldn’t smell anaesthetic gases or hear the humming of the anaesthetic pump. The surgeon then told the court that he had in fact killed the dog with a knife through its heart.

Sewell had a history of appearing for the prosecution in animal abuse court cases. For example, in 1886 he appeared in court as an expert witness on behalf of the RSPCA in a case of ear cropping of mature boarhounds. That prosecution was successful but in this instance Sewell was unsuccessful. The Brown Dog Affair rumbled on for year.

After Louis Sewell joined Sewell & Cousens, he too became an Honorary Veterinary Surgeon at Our Dumb Friends’ League and remained so until his unexpected and early death in 1930.

More recently, two Elizabeth Street partners have had extensive involvement in animal welfare. Until his death in 2019, Keith Butt was a long-standing Trustee of Dogs Trust (www.dogstrust.org.uk). Bruce Fogle was for 10 years Chair of Humane Society International (www.hsi.org) and is President of the West Sussex RSPCA (www.rspca.org.uk).

The Ancestral Home of the French Bulldog Club

French Bulldogs are Britain’s second most popular breed. We see lots of ‘Frenchies’. They have great personalities, but because of their squashed (brachycephalic) faces they have long soft palates that interfere with breathing. And regrettably, most that are seen here at Elizabeth Street have thin, tight nostrils rather than round ones. That makes breathing even more difficult! It means that many, if not most modern French Bulldogs, need corrective surgery, preferably before they are two years old, to breath normally.

The ‘first’ French Bulldog

Alfred Sewell, an illustrious previous occupant of the ‘Veterinary Infirmary’ here at 55 Elizabeth Street was by Royal Warrant, ‘Canine Surgeon’ to Queen Victoria’s son the Prince of Wales.

In 1901, just before the Prince of Wales’ coronation as King Edward VII, his ‘Toy Bulldog’ Peter, elderly and almost blind, reached the end of his natural days. (Peter had an eventful life having previously been operated on at Elizabeth Street by Mr. Sewell after being run over by a butcher’s cart.)

Sewell travelled to Paris and purchased a brindle, white patched, French Bulldog, ‘Napoleon Bonaparte’, from a respected breeder, M. Sedze.

Napoleon Bonaparte

Our veterinary antecedent at Elizabeth Street presented Napoleon Bonaparte to his prestigious client but unexpectedly the King declined Sewell’s gift!

Napoleon Bonaparte captures Frederick Cousens

Alfred Sewell already had many dogs living here at Elizabeth Street including the oddly named ‘Queer Street’, an English bulldog, who was one of his favourites. An 1897 newspaper item says that at Crufts Dog Show that year, ‘Mr. Alfred Sewell’s famous “Queer Street” busily engaged in collecting contributions for a Children’s Cot at the Great Northern Hospital. The cot is to be called “The Doggies’ Cot”, and is endowed and maintained by the dogs of Britain in gratitude for the love which little children bear them.’

So, Napoleon Bonaparte joined the home of Sewell’s new young veterinary partner, Frederick Cousens who with his wife lived around the corner from Elizabeth Street, at 32 Eaton Place. They were enchanted by Napoleon Bonaparte and in 1902 they brought together other French Bulldog owning clients from Elizabeth Street and at a meeting in their home, the ‘French Bulldog Club of England’ was established, with Mrs. Cousens its first Honorary Secretary.

Among the first to use X-rays

Vets here at the Elizabeth Street Veterinary Clinic were amongst the first in the UK to use x-rays diagnostically.

Well over 100 years ago our predecessor, Mr. Alfred Sewell, was taking dogs to an ‘X-ray Photographer’, Mr. W.A. Caldwell at his premises, off Wigmore Street, behind where Selfridges now is. We know from American newspaper stories that in 1913 Alfred Sewell took a dog named Mike, who was uncomfortable and not eating food, to Mr. Caldwell, after Mike’s owner noted that one of his wife’s hat pins was missing. The x-ray revealed a seven inch pin in Mike, who was only 18 inches long!

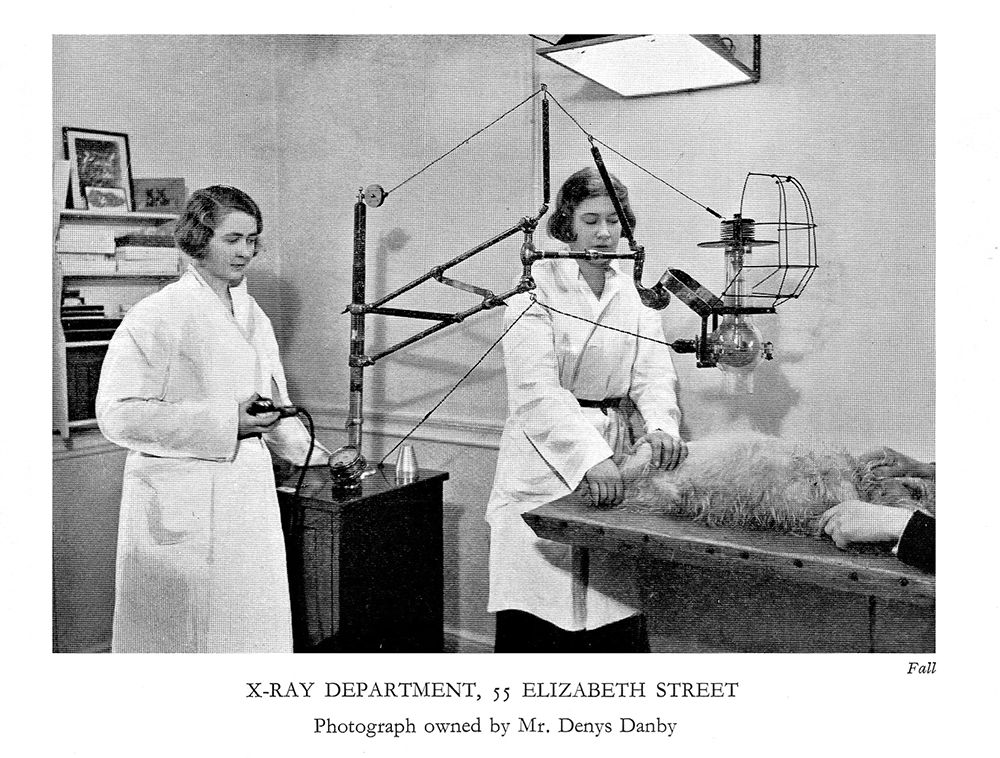

Around 10 years later, Alfred Sewell, his son Louis Sewell and their partner Frederick Couzens, purchased their own x-ray machine, importing it from Chicago. This was one of the first x-ray machines used in a private veterinary facility in Britain.

At that time the risks from exposure to radiation were not yet known, so as you can see from this photo taken around 1930 by Mr. Denys Danby, who succeeded these vets, the nurses did not wear protective lead aprons. In fact, Mr. Caldwell, the x-ray pioneer, died of radiation poisoning and is memorialised at the German Röntgen Museum.

Needless to say modern ‘Ionising Radiation Regulations’ make our digital x-rays safe both for pets and for those who take and interpret the radiographs.

Some of the first 'Canine Nurses' were trained at Elizabeth Street

We know that there have been ‘Canine Nurses’ working at Elizabeth Street for over 100 years. Elizabeth Street patients also benefited from the skills of ‘live-in canine nurses’ at ‘The Distemper Hospital’ near Harrods, on Monpelier Place, South Kensington.

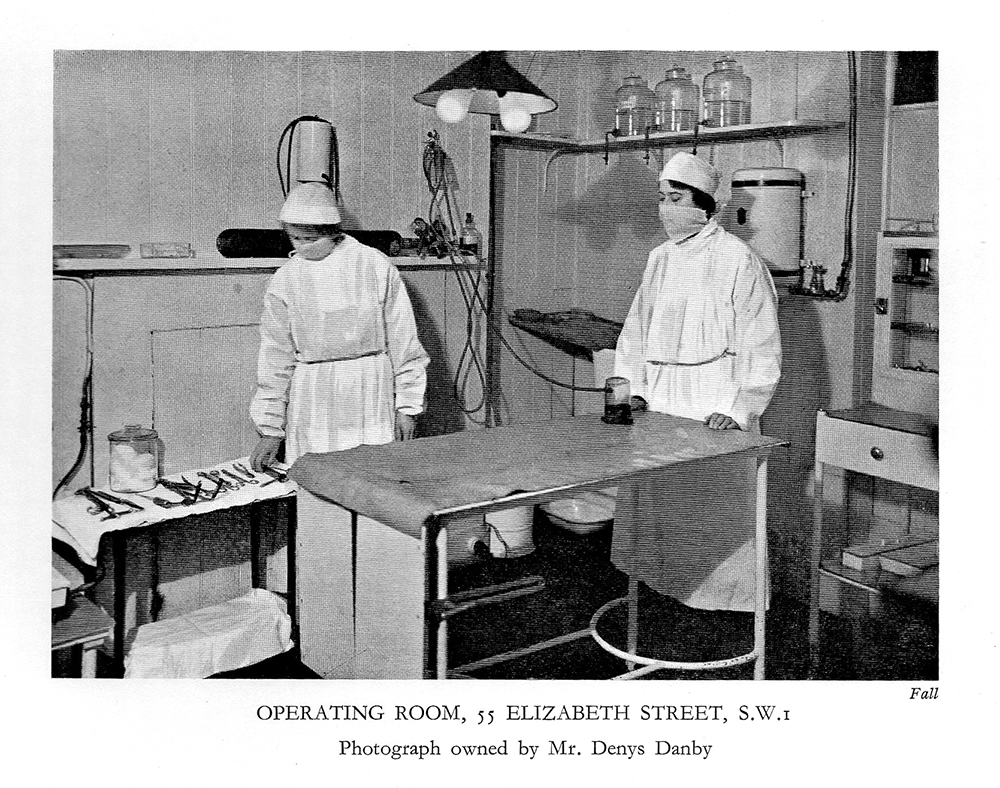

Elizabeth Street’s senior vet Frederick Cousens was a strong proponent of veterinary nursing. In 1934 he tried, unsuccessfully, to get the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) to recognise the term ‘Canine Nurse’. He described Elizabeth Street’s ‘Nursing Home’ as staffed with a medically qualified Hospital Matron in charge and claimed that, ‘this is the first attempt at training women nurses for dogs in this or any other country’. In that year he wrote ‘the RCVS would not entertain the idea. Of course, the Council will come round to my views, probably sooner than later.’ In fact it wasn’t until 1961 that the RCVS recognised ‘Registered Animal Nursing Auxiliaries’ or RANAs.

The nurses you meet today at Elizabeth Street are ‘Registered Veterinary Nurses’ or RVNs. This photo taken by Denys Danby in 1930 (while he was still a student at the Royal Veterinary College) shows two ‘Canine Nurses’ in the operating room at Elizabeth Street.

Denys Danby ran the World War II Dog Training School

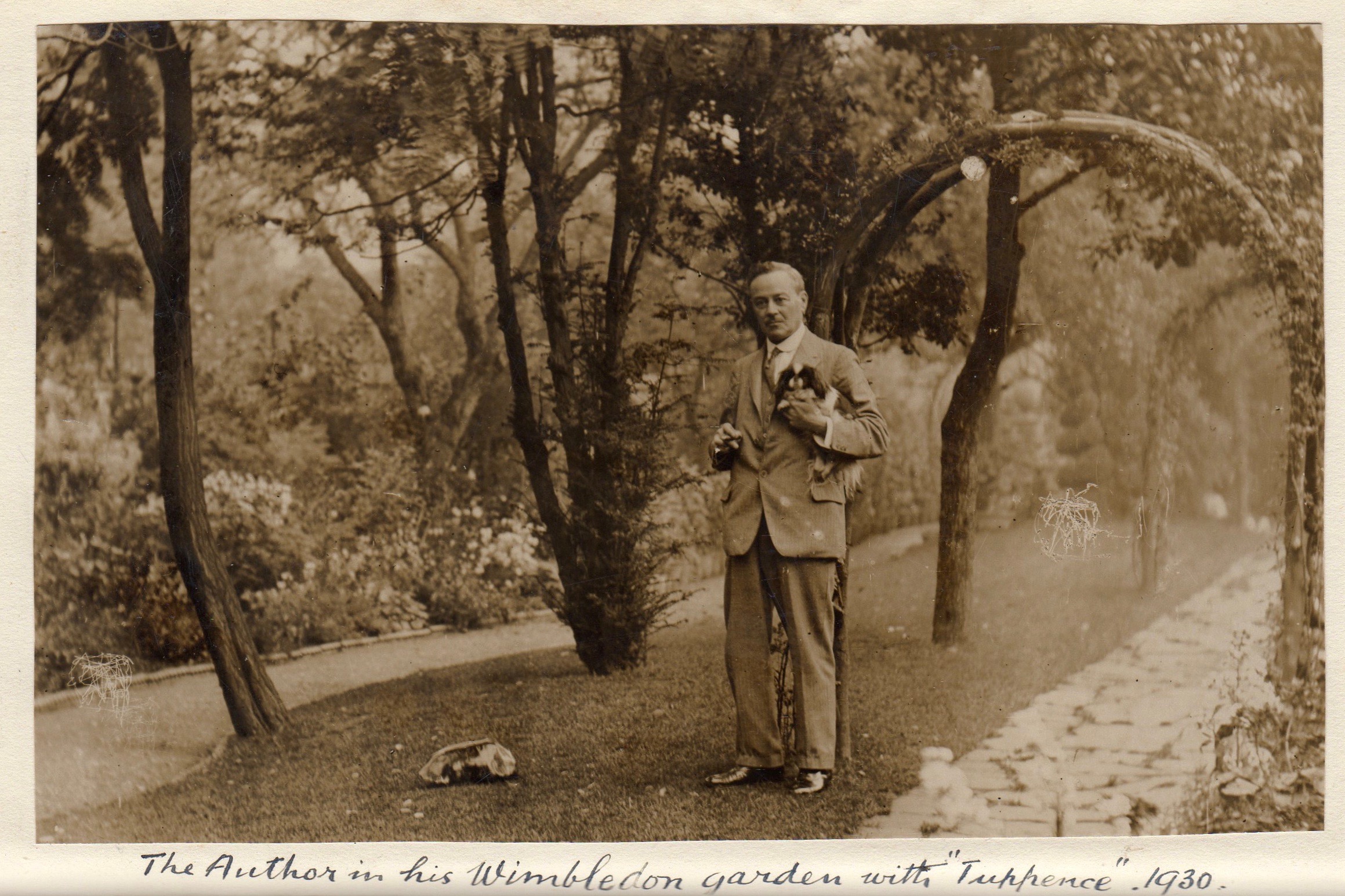

In 1935 Denys Danby, acquired the Elizabeth Street veterinary practice and continued to call it ‘Sewell & Cousens’, the names of the previous owners. The year before, Danby had married Doris Dickens who was Charles Dickens’ great-grand-daughter, an event covered by newspapers in the UK and abroad. This picture is of a press clipping from Muncie, Indiana.

Danby was best known within the veterinary profession for designing a practical anaesthetic mask for dogs that was used by vets for over 30 years. The 1953 edition of the surgery textbook Hobday’s Surgical Diseases of the Dog and Cat says that the ‘anaesthetic mask evolved by Denys Danby is particularly efficient’.

After Edward VIII went into exile in 1938, Danby provided veterinary care for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth’s Corgi ‘Jane’, who gave birth to ‘Crackers’, the present queen’s first Corgi. (At the end of Crackers life in 1953 he visited the dog daily at Clarence House.)

In 1942, many working dogs were needed to support the British Army. Captain Denys Danby took charge of the Army dog training school in Ruislip and only intermittently saw dogs at Elizabeth Street over the next three years. By 1944, when he was Chief Veterinary Surgeon at the War Dog Training School, Greyhound Racing Association kennels, Potters Bar he was calling the Elizabeth Street business ‘Sewell & Cousens and Denys Danby’.

After the war Danby returned to full time work at Elizabeth Street. He continued as the Royal Family’s London vet visiting Marlborough House attending Queen Mary’s dog Bob. He retired to the Isle of Wight in 1958.

Elizabeth Street Vets most illustrious patient

Over the last 200 years we have treated the pets of many famous people. Elizabeth Street vets have travelled abroad to treat the dogs of the Russian czar and German Kaiser, but most of the pets treated lived locally. Downing Street cats have been frequent visitors to Elizabeth Street but one dog in particular, Caesar, stands out as our most illustrious patient.

When King Edward VII succeeded Queen Victoria, the Elizabeth Street vets, Alfred Sewell and Frederick Cousens were, by Royal Warrants ‘Canine Surgeons’ to both the King and Queen Alexandra and to their son the Prince of Wales, the future King George V. Sewell had helped find Caesar for the king after his previous dog ‘Jack’ had died. The king once wrote that Caesar was the best dog he ever had and commissioned Faberge to make a model of his dog.

The accompanying article says: ‘On a visit to Marienbad in August 1907, Caesar was taken ill and Sir Frederick Ponsonby, the Keeper of the Privy Purse, recalled how he tried to persuade the King against the idea of sending for Sewell, a vet from London, at a cost of £200 per day, but His Majesty said “that if his dog was ill he would get the very best man and he did not care what it cost”. In the event Caesar was cured by a vet from Vienna.’

When the king died in 1910, Queen Alexandra, knowing her husband’s feelings for Caesar, instructed that the dog follow her husband’s rider less horse in the funeral cortege to Paddington Station. Caesar walked from Westminster Abbey to Paddington Station, accompanied by a highlander officer. His photo was in virtually every newspaper in the UK. Caesar lived on for another five years but at 16 years of age, he died here at Elizabeth Street, with Queen Alexandra by his side.

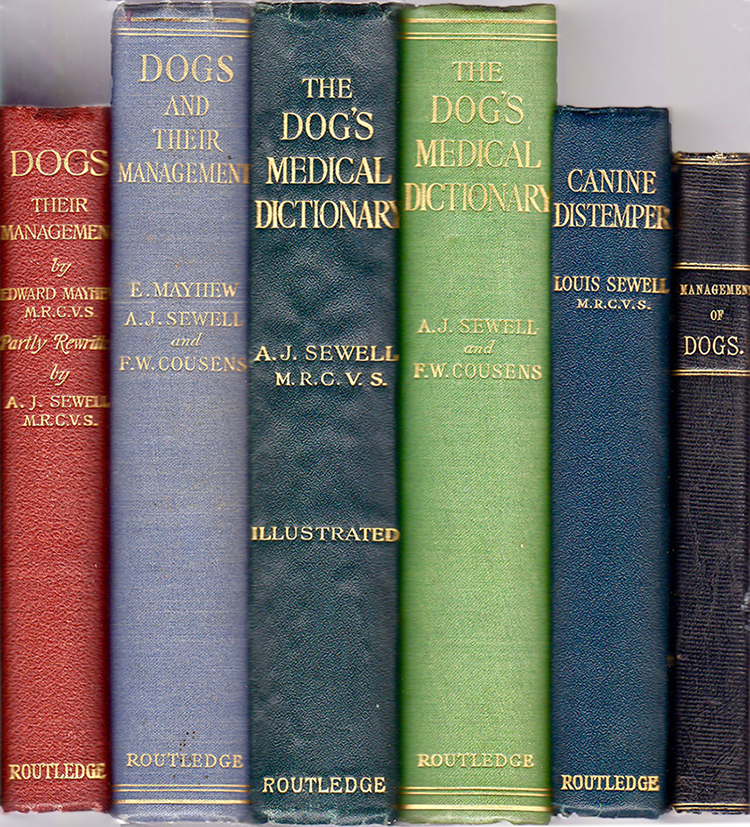

An abundance of dog care books for over 120 years

Alfred Sewell started writing medical articles before he turned to books. In 1891, he wrote the first ever article on ear disease in the dog, published in The Veterinary Journal.

His first book for the general public, published in 1897, was a complete revision of Edward Mayhew’s Dogs: Their Management, which had been first published in 1854.

In 1906, the first edition of his best selling book, The Dog’s Medical Dictionary was published. Revisions of Sewell’s The Dog’s Medical Dictionary, including one co-authored with his partner Frederick Cousens in 1932, were in print for over 50 years!

Louis Sewell, Alfred’s son, published the first book for the public on Canine Distemper.

Bruce Fogle, one of Elizabeth Street’s present veterinary partners continued the Elizabeth Street tradition of writing books for pet owners. His books including The Encyclopedia of the Dog, The Encyclopedia of the Cat and The Dog’s Mindhave been translated into 38 languages.

Actively involved in diagnosing and treating distemper in dogs

Distemper was the most common, fatal, infectious disease in dogs when the present veterinary partners in the Elizabeth Street Veterinary Clinic started their professional careers in the 1960s. Today, thanks to effective vaccines, the disease is rare in the UK but regrettably still common in other parts of eastern and southern Europe.

Dogs infected by the distemper virus have a fever, are lethargic and vomit. They develop diarrhoea, weeping eyes and snotty noses, and then pneumonia. Those that survive may go on to develop muscle twitching or seizures. Some develop hard, cracked pads so another term for ‘distemper’ was ‘hardpad’.

In 1901 the Pasteur Vaccine Company released a vaccine to prevent distemper. Alfred Sewell here at Elizabeth Street used the vaccine, but in time he concluded it wasn’t effective. In 1904 Alfred Sewell publicly challenged the Pasteur Vaccine Company over their claim that their vaccine, against the bacteria Pasteurella canis was effective. Sewell proved to be correct when in the following year Henri Carré discovered the ‘filterable agent’, the virus, that actually causes distemper.

In the meantime, the Elizabeth Street vets continued actively treating dogs for this dreadful disease. In 1915 Alfred’s son Louis Sewell graduated from the Royal Veterinary College. It was World War One and he immediately joined the Army Veterinary Corps, but upon leaving the army in 1920, Lieutenant Louis Durden Douglas Sewell joined ‘Sewell & Cousens’ on Elizabeth Street. Within a few years Louis wrote Canine Distemper: A Practical Handbook. This was the first book devoted completely to the treatment of distemper. Louis Sewell used ‘live-in canine nurses’ at ‘The Distemper Hospital’ near Harrods, on Monpelier Place, South Kensington to care for his patients.

(In 1925 when his father Alfred retired it was Frederick Cousens who acquired the Elizabeth Street Royal Warrants as ‘Canine Surgeon’ to King George V, Queen Mary and Queen Alexandra. Louis Sewell was denied the Appointments, perhaps because of a scandal involving his failed and very public Divorce Petition in 1922, described by the presiding judge as ‘bordering on the frivolous’.)

In the meantime, the magazine The Field set up a Distemper Fund, bringing together the landed gentry, many of whom were clients of Elizabeth Street, and scientists. In 1933, the first truly effective vaccine was produced.

A Centre of Excellence during London's rabies epidemic in the 1800's

There is no rabies in the UK today but there was in the past. In 1885 in London, a rabies epidemic reached epidemic proportions. That year, 80 cases were seen at Elizabeth Street Veterinary Clinic. The epidemic was brought under control through measures recommended by veterinary surgeon, Alfred Sewell.

In early December 1885, a reporter for the Chicago Tribune, visited ‘The Veterinary Infirmary’ on Elizabeth Street and interviewed Sewell about the epidemic.

‘I next visited Mr. Alfred Sewell, veterinary surgeon….at his house … near Eaton Square. His rooms were crowded and there were a number of carriages before his door, while a man on the sidewalk distributed bills, advertising a patent muzzle. When the patients had retired the doctor pleasantly received the correspondent.

“Yes”, he said, “I am busied with consultations this year. I have had seventy-three undoubted cases of rabies under my care, evenly distributed among a variety of breeds (looking at a memorandum-book) – three poodles, four field spaniels, one mastiff, seven collies, thirteen fox terriers, two Maltese, one otterhound and one St. Bernard… I suggested muzzling a fortnight ago to Sir Edmund Henderson, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, pointing out to him the Berlin figures which from 1848 to 1853, showed 272 cases of rabies, and after that date, when muzzling was introduced there were only thirteen cases during the following five years.”’

Alfred Sewell told the reporter he recently visited Paris where he had a ‘long interview’ with Louis Pasteur who that year produced the first effective rabies vaccine. Pasteur was a strong advocate of muzzling. Sewell now advocating the same, became an advisor to the Home Secretary and a Muzzling Order was passed by Parliament.

Sewell supports withdrawing the Muzzling Order

Within a decade, rabies has been virtually eliminated. Having advocated a muzzling order, in the absence of rabies, he now described it as unnecessary and lobbied for withdrawal of the order. In 1897 Sewell wrote that although 50,000 dogs have passed through the Dogs’ Home at Battersea in the last year (where he was a pro bono vet) there had not been a single case of rabies. In a letter to the Editor of The Times in March of that year, he wrote:

‘Dear Sir, In reply to your letter, some of the wire muzzles are very cruel, but a properly fitted one is not so bad… Respecting the Muzzling Order, I think it is quite unnecessary now, especially in London… I wrote to every veterinary surgeon in London in February, asking for the date of the last case of rabies seen, and I had forty-two replies. The last case quoted was November 17th, 1896, and many veterinary surgeons did not see a case last year, and others had not seen one for six months.’

The Muzzling Order was withdrawn two years later.